It’s almost a guaranteed thing, whenever you bump into a fellow Alumni from Guildhall, should you mention tutors of yore, their face always lights up when you say Ken Rea. Ken still teaches Physical Theatre there. We spent the first year moving round the room in unison as the sea, donning a mask and owning the stage, speaking in tongues.

All of his teachings were infused with warmth. All he kept demanding was warmth, generosity and a sense of play from his students. And over the years, a great many household names have passed through his class. From Ben Chaplin, Daniel Craig, Ewan McGregor, Damian Lewis, Joseph Fiennes, Dominic West, Orlando Bloom, Michelle Dockery and Lily James.

I always felt a little sorry for all the actors who had never had the chance to work with him, inspirational and supportive as he was. There’s certainly a whole generation of actors who remain thankful for his teachings.

Well, the good news is, having taught for as long as he has (three decades), he recently released an updated version of his book about acting, through Bloomsbury Methuen, called “The Outstanding Actor – Seven Keys To Success”.

Not long after leaving Guildhall, Ken invited me to see a production by Sankai Juku, at the Sadler’s Wells, if memory serves. Other than the fact that Ken was recommending it, I knew nothing of what I was about to see, so whilst we awaited the curtain, Ken offered me the programme, that I might read the blurb. Hugely instructive about the Japanese Butoh Dance company formed in 1975, I reached the bottom to find it had been written by Ken. It turns out he has also contributed as theatre critic for the Guardian for 15 years, as well as writing for The Times.

Credit: https://www.sankaijuku.com/?lang=en

I was privileged to read an early draft of The Outstanding Actor and was really impressed by what I read. It took me back right to the fluorescent lit days in the drama corridor at Guildhall, now all gone: They’ve moved over the road to a spanking new purpose-built premises on the site of the old Fire Station in Silk Street.

It’s an outstanding insight into the workings of an actor. And not just any actor, but good actors, with input from the likes of Dame Judy Dench, Al Pacino and Nicholas Hytner. The seven chapter headings read: Warmth, Generosity, Enthusiasm, Danger, Presence, Grit and Charisma.

I mean, forget about acting, who doesn’t want to get a handle on all that!?

However the landscape of acting changes, be it theatre, radio, film or television, the means of telling any given story well remains paramount. It’s the storyteller we invest in, with whom we are asked to relate to. I think it quite telling that whenever anyone talks about the greatest, the most famous lines in movie history, no one remembers the poor writer, only the actor.

‘We’re gonna need a bigger boat’.

‘Say hello to my little frienn’.

‘I’ll be back’.

I recommend The Outstanding Actor to anyone really, it’s an incredibly interesting read, whether you have aspirations to act or not, but especially if you are an actor.

Ken also periodically runs seminars - open to anyone, and also a comprehensive online course.

You can find out about these by going to his website:

https://www.kenrea.co.uk/acting-tutor/

Continuing the dip into my Film School dissertation…

Anatomy Of A Flop 006

Chapter Three ‘POV’

My upbringing and education up to this point has been entirely through the English State School system and although I had experienced racism from a very young age, I didn’t really think much further about it for many years beyond it being a simply personal, or individual thing.

However, inspired from about the age of five as I was to be an actor, it was only when I came out of drama school 22-years later, convinced that I was an ‘actor’ and could play anything from a five-year-old boy to a 75-year-old woman that the proverbial scales then fell from my eyes. I loved Shakespeare but even though I’d attended Guildhall - a classical training - it quickly became apparent that I would only work as and when a specifically Asian part on TV, film, stage, or even radio was being cast.

I tried my best to avoid the stereotyped and mostly negative roles pushed my way and selected roles that were just characters in the piece, not necessarily defined by their being ‘Asian’. These proved few and far between and at times – purely to pay the rent - I was forced to take a stereotypical role, which ordinarily I would have rejected.

For me, things were further convoluted by the fact that I had been adopted at a very young age into a white, middle-class family. On the one hand this meant that my view of ethnicity was that it made absolutely no difference to ones ability or sensibility. On the other, it highlighted that the roles available to me as an actor were nearly all Asian, requiring a language, an accent, or at least an innate knowledge of what it meant to grow up as ‘Indian’.

Credit: https://www.theatreticketsdirect.co.uk/venue/234/the-kiln-theatre-(formerly-the-tricycle-theatre)

The situation was illustrated time after time, as I would go from audition to audition. I recall one for a production of Macbeth at the Tricycle in Kilburn, with a director well known for his casting of non-white actors (or as we would have it, known to ‘work well with The Ethnics’), where I was asked to read a Macduff monologue. I did so and he (after an embarrassed pause as he wondered how to phrase the next question) asked me if I would do it as I might ‘normally talk’. I explained that that was how I ‘normally talked’.

His tone changed, implying gently that I might be fibbing and tried a different angle, saying that the ‘text sprang to life…’ when one used one’s ‘…own accent’ and he then suggested - on viewing the expression on my face - that might I do it with the accent that my father has.

With a sinking feeling I knew, even as I said that my father spoke pretty much as I did, that I wasn’t getting the job and moreover, that he was convinced I was lying, trying to be something I wasn’t but that in fact, he wasn’t looking past my colour... My training, my truth, irrelevant. Even worse, he was actually judging me for having turned my back on his idea of what my ancestry was.

Things were no better the other way around. I recall going for a major British-Asian film and being asked by the (Asian) auditioner what other languages I spoke. I replied ‘a smattering of French…’ now with that familiar sinking feeling, I already knew where he was leading. I certainly didn’t feel I needed to apologise for my circumstances, that I was an actor and could do whatever was necessary for the job, if he could be bothered to find out about me.

It was abundantly clear from this moment, as he realised I didn’t speak an Asian language, that he also had no respect for anyone who ‘turned their back on their roots’ and that I therefore wasn’t going to get a part in East Is East.

Credit: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0166175/mediaviewer/rm2119456000/

There was another side to this conundrum, whenever I have gone up to play a part on TV not based purely on racial stereotype, by the time the programme is made, even if the part was specifically written for an Asian, nine times out of ten, it had been cast white. Someone down the line had expressed an opinion, or nervousness as to the casting.. and that’s all it’s taken for the decision to go ‘safe’.

A prime example of this was the 1994 series Crown Prosecutors. One of the characters was an erudite, intelligent young man of Indian descent. The writer had done his research and written a well-rounded role, which just happened to be Asian. Fantastic. In the interview I met the casting agent and the director. The director was very pleased and actually articulated that I was very reminiscent of the guy they had actually based the character on.

I left the audition very buoyed up by the experience, pleased that I had hung on and not gone for a steady job. Shortly thereafter, an actor known to me landed a part on the series so I asked if they’d cast the part I was up for... There was a moment’s confusion as he tried to work out which the ‘Asian part’ was.

To our growing consternation, we realised they’d cast Michael Praed, famous for playing Robin Hood in a long running series of the Eighties, Robin Of Sherwood.. I spoke to my agent and she said word had come back that they simply ‘hadn’t found anyone suitable to play the part’. I could have named five off the top of my head.

The other side of the coin was there were certainly more than one British-Asian actor ‘painting themselves brown’ purely to get the gig. I couldn’t blame them. It was so hard out there, there really wasn’t enough work to go around and the work there was, was usually badly paid: often worse than our white counterparts, though this was only ever a point of discussion in hushed tones between other Asian actors.

This of course meant there was a magnified intensity, greater competitiveness and resultant insecurity, compounded by the use of the same actors time and again, as the bodies responsible for casting the latest TV offering came to rely on the safe, the tried-and-tested- as most casting these days is. There really was an ‘Us and Them’ mentality, borne out of fear and ignorance.

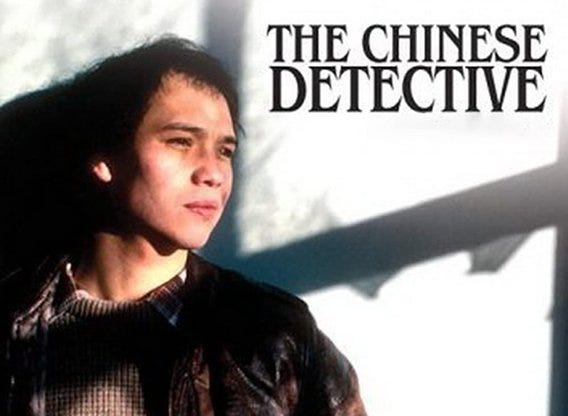

As previously mentioned, whatever was on TV was in the playground the next day. I grew up watching trailblazer David Yip in The Chinese Detective. I also grew up in a very white area of Britain, in Bedford. There weren’t any Chinese living in my area and in a school of 1100 pupils, not a single Chinese kid. However, I do know that if there were, he would have gained significant kudos, a validation of his identity, from the show. There were no other Indians either and just one black guy.

Credit: https://next-episode.net/the-chinese-detective

On 5th August 2003, I found myself writing a second letter to Greg Dyke concerning an episode of Roger, Roger which I’d watched in open-mouthed shock which turned rapidly to disgust at the ridiculously stereotyped portrayal of British-Asians.

It concerned the clandestine planning of an arranged marriage of a young man at the hands of his parents - I got a response of sorts, placatory and grateful for my comments. I have to say, I do think perhaps Mr Dyke would have gone on to make some excellent changes had political events not curtailed his tenure.

This was the second time I’d written to him. the first being to state for the record the conversation I’d had with an unidentified woman working in the BBC Film Dept. I’d called up following an invitation I had sent out to sales agents and distributors, concerning a screening of Offending Angels in January, 2002. Receiving no response from (the then Head of Film) David Thompson’s office, I was pursuing whether he was available to attend.

She politely advised he was out of the country over the date in question. I then asked whether a representative could come in his stead.

Silent for a moment, she then pondered out loud…

‘Offending Angels.. Offending Angels... that has Asians in it doesn’t it?’

‘One of the leads is Asian, yes.’ I replied.

‘Yes.. yes.. No. No, I don’t think so, thank you.’

With Andrew Lincoln - Offending Angels.

This is a verbatim transcript of our conversation. I did not suggest in my letter to Mr Dyke that what she had said could be construed as openly racist (to give her the benefit of the doubt, I think she was trying- off the top of her head- to ‘place’ the film), but I did suggest that the BBC should seriously address how they illustrated their decision-making process to filmmakers phoning in…

Greg Dyke’s response was to ask whether I wanted to take matters further, which I of course declined.. however unbelievably shocking it was, I wasn’t after someone’s job.

For me personally, as a result of writing both the first and then the second letter, I realised a far more serious thing; that I was in grave danger of letting this litany of frustration and disappointment eat me up - from the inside.